All the way to the hospital

The lights were green as peppermints.

Trees of black iron broke into leaf

ahead of me, as if

I were the lucky prince

in an enchanted wood

summoning summer with my whistle,

banishing winter with a nod.

Swung by the road from bend to bend,

I was aware that blood was running

down through the delta of my wrist

and under arches

of bright bone. Centuries,

continents it had crossed;

from an undisclosed beginning

spiralling to an unmapped end.

II

Crossing (at sixty) Magdalen Bridge

Let it be a son, a son, said

the man in the driving mirror,

Let it be a son. The tower

held up its hand: the college

bells shook their blessings on his head.

III

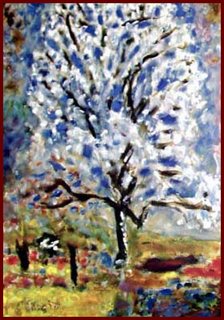

I parked in an almond's

shadow blossom, for the tree

was waving, waving at me

upstairs with a child's hands.

IV

Up

the spinal stair

and at the top

along

a bone-white corridor

the blood tide swung

me swung me to a room

whose walls shuddered

with the shuddering womb.

Under the sheet

wave after wave, wave

after wave beat

on the bone coast,

bringing ashore - whom?

New-

minted, my bright farthing!

Coined by our love, stamped

With our images, how you

Enrich us! Both

you make one. Welcome

to your white sheet,

my best poem.

V

At seven-thirty

the visitors' bell

scissored the calm

of the corridors.

The doctor walked with

to the slicing doors.

His hand is upon my arm,

his voice - I have to tell

you - set another bell

beating in my head:

your son is a mongol

the doctor said.

VI

How easily the word went in -

clean as a bullet

leaving no mark on the skin,

stopping the heart within it.

This was my first death.

The 'I ' ascending on a slow

Last thermal breath

studied the man below

as a pilot treading air might

the buckled shell of his plane -

boot, glove and helmet

feeling no pain

from the snapped wires' radiant ends.

Looking down from a thousand feet

I held four walls in the lens

of an eye; wall, window, the street

a torrent of windscreens, my own

car under its almond tree,

and the almond waving me down.

I wrestled against gravity,

but light was melting and the gulf

cracked open. Unfamiliar

the body of my late self

I carried to the car.

VII

The hospital - its heavy freight

lashed down ship-shape ward over ward -

steamed into night with some on board

soon to be lost if the desperate

charts were known. Others would come

altered to land or find the land

altered. At their voyage's end

some would be added to, some

diminished. In a numbered cot

my son sailed from me; never to come

ashore into my kingdom

speaking my language. Better not

look that way. The almond tree

was beautiful in labour. Blood-

dark, quickening, bud after bud

split, flower after flower shook free.

On the darkening wind a pale

face floated. Out of reach. Only when

the buds, all the buds were broken

would the tree be in full sail.

In labour the tree was becoming

itself. I, too, rooted in earth

and ringed by darkness, from the death

of myself saw myself blossoming,

wrenched from the caul of my thirty

years' growing, fathered by my son,

unkindly in a kind season

by love shattered and set free.

Jon Stallworthy

___________________________________________________

A longer poem this time, and one that means a great deal to me. I was so moved by it that I learned it by heart and have carried it around in my head for over 30 years. I love it both for its emotional weight, and for the richness of its imagery.

It tells a story and one that any reader can relate to: a father rushes to the hospital for the birth of his son, and is told that the son has Down's Syndrome.

Stallworthy calls it the most straightforwardly autobiographical of his poems.

Look at how the emotions shift from stanza to stanza. As the father drives to the hospital, there's a real sense of elation as he contemplates his son's birth and the passing on of new life down the generations. (I love the image of the blood running under arches of bone - a river of life, flowing from father to son across the ages.)

By the end of stanza 4 I'm all choked up when I reach this expression of love:

"Welcome/to your white sheet,/my best poem." What more fitting tribute from a poet! (Stallworthy later said that the words were an unconcious echo of Ben Jonson's elegy,

On My First Son):

But then there are the doctor's words to shatter his joy.

"How easily the word went in -/clean as a bullet/leaving no mark on the skin,/stopping the heart within it." These words bring home the emotional impact of the news.

Isn't it just so true that at the moments of greatest trauma we feel distanced from our physical body, as if we are observing ourselves from a distance? Stallworthy compares himself to a pilot treading air after being ejected mid-air, and watching the wreck of everything from above. Part of him dies at that moment:

"This was my first death".

In a sense too, there's a bereavement that he has to handle. The son of his hope and imagination is drifting away from him, to be replaced with someone who will never speak his language (in a metaphorical sense). But from that pain grows transformation and new awareness. And he realises that he'll learn a different lesson of love from his handicapped child.

Just as physical objects become invested with greater meaning at moments of emotional crisis. (We seem to notice things in much greater detail.) The blossoming almond tree outside the hospital seems complicit in everything.

I seldom reach the end of the poem with dry eyes. Stallworthy is as powerful a story-teller as any fiction writer.

Labels: bibliobibuli's choices, poems about disability, poems about fatherhood, poems about parenthood

Malika Booker was in Malaysia last year both to perform and to run workshops, and I had the pleasure of interviewing her for StarMag, which is where this poem appeared.

Malika Booker was in Malaysia last year both to perform and to run workshops, and I had the pleasure of interviewing her for StarMag, which is where this poem appeared.